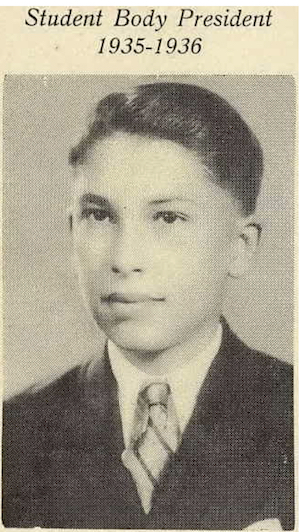

Dad

Always dignified, yet with the tough American Indian swagger and southern drawl, looking as if you were ready to pull out a knife and fight at any moment; the boss man, the gentleman, you were always called “Sir.”

Just you and me at Brooks Brothers buying your suits. You compelled service and attention. The time you got the one with the watermelon pink pinstripes because I picked it out.

Holding a knife over the hand of a bus boy when he went to take your plate before you were finished eating, "What, you short of dishes?"

When my hand was grasped firmly in yours, I always felt safe, because I was with you. Walking down the street, you were always aware, always in control, pointing out drug addicts, panhandlers.

And it wasn’t just me you looked after. It was all the women on the bus going downtown. You’d alert them to any roving pickpockets. The time you rescued the woman falling from the atrium balcony on the top floor of the Santa Fe Building where your office was.

Playing cards with me and my sister like you were a dealer in a casino: Black Jack, Gin Rummy.

“It doesn't matter if you win or lose. It's how you play the game.”

Jogging behind women joggers in short-shorts. “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

In the kitchen, “Hey good looking, whatcha got cookin'?’”

At the dinner table, "Can I sell you some peanuts, popcorn...?

Sprinkling dried red peppers on your pizza at My Pi. Me or my sister sitting next to you so we could mop the sweat off your bald head.

Looking in the mirror, combing what was left, saying, “I just can’t do a thing with my hair.”

Getting my sister and me to help you with the your crossword puzzle while we were riding the bus.

Smooching and cuddling in movie theaters, the movie “Tootsie."

Laughing at "Some Like it Hot" and "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes."

You were brutal and blunt, sarcastic and funny, full of stories, rarely believed, no doubt misunderstood. You told about growing up on the reservation. Your mother growing and cooking all your food and sewing all your clothes. The hobos coming by your small shack during the Depression and your mother feeding them all. Hustling marbles for milkshake money. Swallowing oysters on a fishing line as initiation for the debate club. Paddling fraternity brothers strung together in a line to pee. World War II stories of torpedoes and pulling the bodies out of the water and drinking and who knows how you ever survived and the nightmares kept coming back and never went away.

Married to your first wife, your high school sweetheart, the dancer. “Women,” you said, “can’t live with them; can’t live without them.”

You were a pool hustler, a golf hustler, a money man. You knew you had to “go along to get along.” You could always make a friend.

My mother, your second wife, would say you were a charmer, a manipulator. She thought that you always knew how to get your way.

But I think the world never went your way, but you made your way, though you saw all the things that were wrong. The world was full of stuff people didn’t need, second homes, luxury cars. People taking advantage of other people; the poor always getting the short end of the stick.

Drinking martinis in water glasses so the boss wouldn’t know you were drinking. Later I joked with you, “There’s nothing like a white man to drive you to drink.”

Waitress at the "greasy spoon" in your office building. You had her trained to bring you your orange juice in the morning. Waitresses always flirted with you.

Things you would say: “White man speak with forked tongue.” “Paper doesn’t refuse ink.” “A stiff prick has no conscience.” “These Harvard MBAs don't know enough to pour piss out of a boot.” “You can’t treat people that way, or you’ll have a revolution.” “I always treat everyone like I might be working for them someday. You never know what will happen.” "It takes all types of people to make the world go round.” “Some people won’t like you just because of the way you part your hair.” “Keep a lip upper stiff.”

You never lost the mentality of the token minority, achieving success through hard work and being smarter than everyone else. Making your way trying to hold on to your cultural values while being blackmailed into betraying them on a daily basis. The dual mindset; the cognitive distance/ dissonance; hiding and being proud at the same time.

"There are more important things in life than money. These people act like they're such good Christians and all they do is fight about money. Life is too short to fight about money."

Paying to get into D's play, a small production at a local theater, even though he would have let us in for free, because paying if you could afford it was the right thing to do.

You were a fan of Will Rogers and Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. Merle Haggard's "Okie from Muskogee" was the family theme song.

You never let us forget that we were American Indian: the stories you would tell; the books, jewelry, dolls you would give us.

You thought feminists were trying to destroy the family and the communists were trying to take over the country and destroy the “free enterprise” system. Horrified as I read Germaine Greer and Karl Marx.

You always listened to me talk about ideas.

The time I explained anarcho-syndicalism to you over dinner and you thought it made some good points, such as workers knowing more about how to manage work than bosses.

When, as a teenager, young adult, I complained of men manhandling, you said, “Well, you're an attractive gal. You’re just going to have to learn to deal with it.”

You called me "rebel with a cause.”

Told me I should be a lawyer because I loved to argue.

You never told me what to do, though you would listen, because, you said, "Nobody can ever tell you what to do, because you've already thought it through backwards and forwards and every which way. Somebody could tell you to “go jump in the lake,” but you wouldn't do it unless you thought it over first.”

When discussing some dilemma or life choice, you would listen and then say, "You've got to decide what you want to do."

You carried an essay I wrote in Sunday school when I was very young in your pocket. You told me you thought I was a wonderful writer. And you gave compliments rarely, always told the truth, often critical, so I know you meant it.

Carried around a picture of me riding a donkey in Greece and would say to people, "Wanna see a picture of my daughter sitting on her ass?"

When mother tried to push me, you would say, about whatever it was, "She'll do it when she's ready.”

When the school complained that I was too quiet, not assertive enough, you said, "We don't want her to be aggressive. That's not her nature. She knows the answers. If you ask her a question, she'll tell you."

Sunday mornings you would make us pancakes. For the dolls, too. Then take us to Sunday school.

Waking us up. "What am I going to do with this big sack of potatoes? How are you going to get your cornbread made, sleeping in the sun all day?”

When we were little, dancing down the sidewalk doing twirls coming home from the diner on the corner.

People often thought you were our grandfather. Maybe, for a while, we kept you young.

When I was a young teen, at parties and events you would introduce me as "the woman I live with," getting a kick out of letting people think I was your live-in girlfriend.

I got married just in time to have a husband to hold my hand at your funeral.